春から秋へ

日本における循環型経済の衰退を目にするのに、そこまで時計の針を巻き戻す必要はないのかもしれない。小津安二郎監督の『晩春』(1949年)には、木材、天然繊維、皮革、紙、陶器、石、シンプルな金属など、大部分がリサイクル可能なバイオマテリアルによって構築された、資源豊かな物質社会が描かれています。一方で同監督の作品『秋刀魚の味(英題:An Autumn Afternoon)』(1962年)のある予告編は、工場の煙突がもくもくと煙をたてる映像で幕を閉じられており、プラスチックやその他の高度に加工された素材によって、次第に特徴づけられていく経済状況を示唆しています。

日々の暮らしにおける循環型社会からの脱却は近年、急速に、しかもほぼすべての地域で起こっています。日本では、コンビニのおにぎりから新幹線の車内で提供される紙ナプキンにいたるまで、包装や贈答という統合的かつ包括的な文化的伝統が、広く普及したプラスチック包装に体現されています。これは岡秀行が1975年に、How to wrap 5 eggs という本で紹介した、伝統的な実践を美しく縁取ったものからはあまりにもかけ離れたものです。このことは「超大量生産のニーズに応えるには、伝統的な天然素材はあまりにも手に負えない……そして私たちは次から次へと、従順で予測可能な合成繊維に置き換えてきた」と、先の書籍に寄稿したジョージ・ネルソンを嘆かせました。

おにぎりからコンビニへ

これは単に、形あるものをどうパッケージするかという問題ではありません。手にしたプラスティック包装のおにぎりから、ふと顔を上げてみれば、コンビニにあるほぼすべてのものが線形経済を体現していることに気づくでしょう。棚に並ぶ身近な商品はもちろんのこと、もっとまわりを見渡してみれば、インテリアの素材、家電製品、サービスインフラ、建物そのものも当てはまります。これらのシステムを「糸を引く」ように、あらゆる方向に解きほぐしてみると、店舗にとぎれることなく商品を補填する物流ネットワーク、商品を生産する工場およびその原材料の調達過程など、あらゆる側面に出会うことができるでしょう。

明らかに、これらは日本だけの問題でありません。しかし、おにぎりとコンビニ、すなわち包装された軽食と、構築環境(built environment)という2つのレイヤーは偶然にも、あるローカルの力学を表しています。

製品パッケージのスケールを超えて、日本における構築環境のメタボリズム(=新陳代謝)は実にユニークで、絶えず変化するよう最適化されています。更新されつづける傾向があることは文化的な観点からも非常に有益であり、日本の多くの都市を特徴づける、複雑なダイナミクスを可能にしています。実際、木材に見られるメタボリズムは、リジェネラティブなものでありうる可能性を秘めています。しかし、この70年ほどの間、このダイナミズムがコンクリートやプラスチック、鉄に追いやられてきたこともまた事実でしょう。私たちはこの慣行を早急に再考しなければなりません。

名古屋にある、Nori Architects(川島範久建築設計事務所)が設計したGood Cycle Buildingは、杉の丸太、土壁、そして築30年のビルの改築によって出てきた「廃材」を廃棄するのではなく、その場で使いなおすというオルタナティブなあり方を提示しています。このリノベーションには、敬意と技術に導かれたケアとリペアが前面に押し出されています。

しかし、システミックな変化は建物の構造だけでなく、自然との類縁関係を含め、私たちがどのようにともに生きていくかという問題の構造にも関係しています。隈研吾は、素材とのより深い関係を模索するなかで、「料理人は身体を忘れることはないが、建築家は身体を忘れることが多い」と指摘します。この例えは言い得て妙でしょう。私たちは、自分たちがその一部であり、そして都市もまた、それによってつくられているにも関わらず、資源のフローを忘れがちです。しかし優れた料理人は、野菜の原産地はどこなのか、どの屋上で採れたハーブなのか、どの養蜂家の蜂蜜なのか、どの樽で仕込まれた味噌なのかを正確に把握しています。

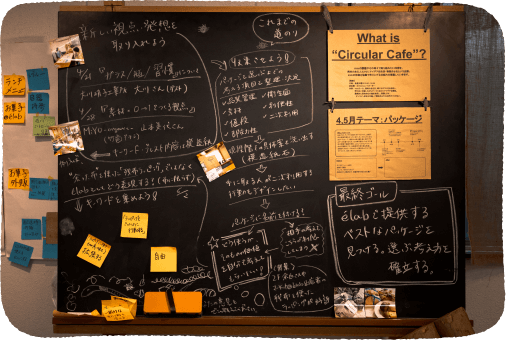

東京の蔵前にあるélabでは、料理人が目の前でそのようなシステムを編み出し、料理のあらゆるディテール、そしてそれがいかに循環しているかを正確に説明してくれます。たとえば、élab のパンには、カカオハスク(豆の外皮)のかけらがさりげなく練り込まれています。これは近くのダンデライオン・チョコレート工場で使い道を見つけられなかった、製造工程の唯一の余剰物です。ダンデライオンはこのカカオハスクをすぐ近くの élab に送り、élab は慎ましやかな錬金術でパンに練り込んでいるのです。

小さなものづくり工房や工芸品、店舗が立ち並び、資源豊かで機知に富んだ蔵前では、循環型のネイバーフッドを想像することができます。情報ネットワーク、軽やかなロジスティクス、順応性のある都市デザイン、そして理想を共有する献身的な個人が、この場所全体を新たに紡ぎ出すことができるでしょう。élab からダンデライオン、そして農家や仕入先のネットワークへとつながる見えない糸が増殖し、多様化することで、蔵前は日本的な特徴を有する循環型社会へと変貌を遂げるかもしれません。

ムーブメントからムーンショットへ

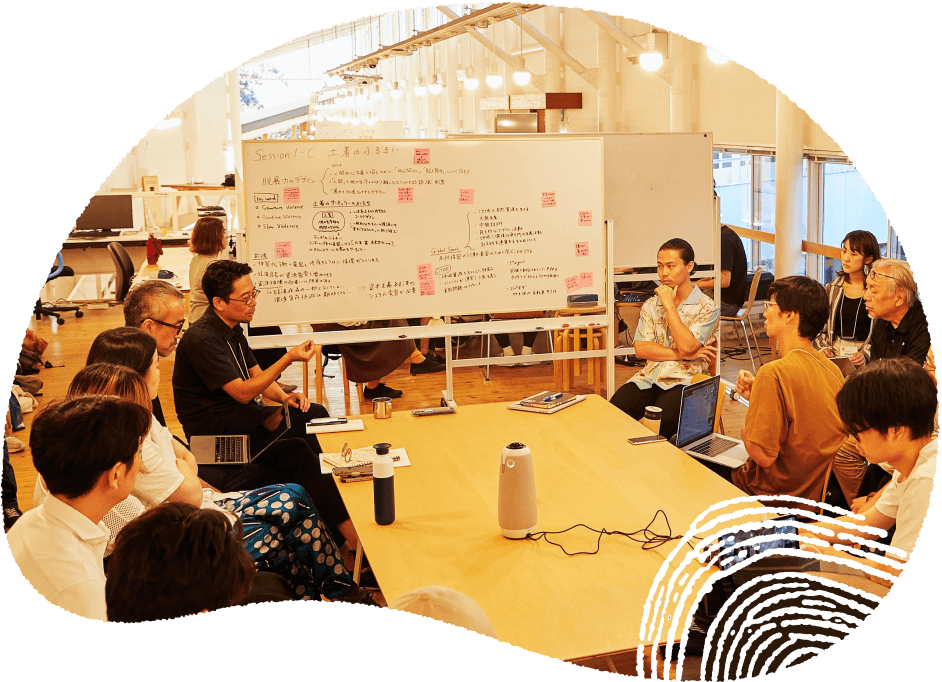

悲しいことに、これらの素晴らしい例はメインストリームとは言い難い。大規模な循環型社会は、ビジネスと産業、社会と文化、そして共有物に対してどのように協働で意思決定を行うかについて、まったく異なる枠組みを必要とします。しかし、こうしたスケールの課題にワクワクすることもあります。私たちの旅は、Nori Architects や élab が日々行っている、経験をともなった慎ましやかな実験から始まるかもしれない。ただし、広範囲に及ぶシステミックな変化は、政策や規制、資金調達といった「トップダウン」の上部構造を無視して、勇気あるいは関心をもって課題に取り組む個人の「ボトムアップ」の行動のみによって、達成されることはありません。このようなアプローチは非倫理的であるだけでなく、逆効果であり、2つの弾み車が互いに逆行することになるでしょう。スウェーデン政府が推進するミッション志向型イノベーションのプロトタイプは、おそらく「ムーンショット」のような技術的なプログラムと、社会運動のような参加型で場を起点とした(place-based)アクションとのバランスを取りながら、これらの運動を結びつける方法のヒントを与えてくれるでしょう。

ムーブメントとムーンショットの両輪をともに動かしていくにはどうしたらいいでしょうか。そこにはシンプルかつ参加型で、リジェネラティブな成長を前提とした、スーパーローカルな事例の多様なネットワークと、従来の経済モデルに支えられたテクノロジー主導のプロジェクトや、より複雑な資源のフローとが、どのようにバランスをとりうるかを見極めることが含まれるでしょう。もしこのポートフォリオを管理するストラテジックデザインの能力があれば、政府はこうした一連のアプローチをさりげなく刺激し、方向づけることができます。そのためには「ガバナンスとは何か」という新しい考え方が必要ですが、ここではドネラ・メドウズのこのアドバイスを思い出してみましょう。「システムチェンジにおける最も強力なレバレッジポイントは、これらの基本原理が重要になります。私たちは関与するガバナンスの『トップ』と、多様で多元的なプロトタイプの『ボトム』をつないで、一つの輪を形成しなければなりません。」

秋から春へ

より具体的には、ニッチな製品からメインストリームな製品へ、蔵前における近隣との親密な関係性と環境から日本のすべての産業・農業のネットワークへ、循環型社会を構築していく必要があります。そして使い捨て包装から再生可能なサプライチェーンへ、Good Cycle Building から構築環境に関わる産業全体の変革へと移行していく必要があるのです。

これらの課題は、その規模、多様性、システム的な相互関連性から、重要な問いを提起しています。多様な知識体系を横断するオープンマインドな探求は、日本の精神に根ざしたサーキュラーデザインの実践のために種をまくことができるでしょうか? 今日の使い捨て社会以前の過去から、どのようにして有意義なインスピレーションを得ることができるでしょうか? そして現在、élab やその仲間たちのような事例を耕し育てるにはどうしたらよいのでしょうか? そして、未来のムーンショットとムーブメントを融合させるにはどうしたらよいのでしょうか? これらすべてにおいて、私たちは新しいメタボリズムのダイナミクスを見ることができるのではないでしょうか? 真に独創的なサーキュラーデザインの実践は、日本の秋の午後を、新しい春として再び開花させるかもしれません。

Spring to Autumn

Perhaps we need not wind the clock that far back to see the fading of a Japanese circular economy. The setting for Yasujiro Ozu’s Late Spring (1949) depicts a resourceful material society constructed largely from recyclable biomaterials—wood, natural fibres, hides, papers, ceramics, stone, some simple metals. Whereas the cinematic trailer for Ozu’s Autumn Afternoon (1962) is book-ended by footage of belching factory chimneys, suggesting an economy increasingly articulated via plastic and other highly processed materials.

That move away from everyday circularity happened rapidly, recently, and almost everywhere. In Japan, integrated and holistic cultural traditions of packaging and gifting become embodied in pervasive plastic wrapping, of everything from onigiri in konbini to the paper napkins offered aboard a shinkansen. This is a long way from Hideyuki Oka’s 1975 book How To Wrap Five Eggs, a publication of beautifully-framed traditional practices that led George Nelson to lament “To suit the needs of super mass production, the traditional natural materials are too obstreperous . . . and one by one we have replaced them with the docile, predicable synthetics.”

Onigiri to konbini

Yet this is not simply about how we package the tangible everyday. Look up from the plastic-wrapped onigiri in your hand, and virtually everything else in the konbini embodies the linear economy. All the immediate products lining the shelves, of course, but looking wider, the interior’s materials, its appliances, the service infrastructures, the building itself. We might ‘pull the thread’ on these systems, untangling them in all directions, and so encounter every aspect of the logistics networks that continually refill the store, the industrial facilities that produce the goods, and the extractive processes that their raw materials are derived from.

Clearly, these are not simply Japanese issues. Yet those two illustrative layers — onigiri, konbini; wrapped snack, built environment — do happen to represent particular local dynamics.

Beyond that product packaging scale, the metabolism of Japanese built environments is unique, optimised for constant churn. This tendency for renewal can be highly beneficial from a cultural point of view, enabling the complex dynamics that define many Japanese cities. Indeed, such a metabolism expressed in wood is potentially regenerative. Yet for the last 70 years or so, that dynamic has been lashed to concrete, plastic, and steel instead. Those practices we must urgently rethink.

Good Cycle Building in Nagoya, by Nori Architects, embodies an alternative trajectory, with a cedar log, earth plaster, and ‘waste material’-led retrofit of a 30-year old building transformed in-situ rather than discarded. The renovation has care and repair to the fore, guided by respect and skill.

But systemic change concerns not only the architecture of a building, but the architecture of the problem: all aspects of how we might live well together, including our kinship with nature. Searching for this more meaningful relationship with materials, Kengo Kuma pointed out that “A cook never forgets the body but an architect often does”. Kuma’s choice of analogy is apt. We have often forgotten the material flows that we are part of, and that the city is made of. Yet a good cook knows precisely the provenance of vegetables, which rooftop the herbs are from, whose bees made the honey, who made the jar for the miso paste.

At elab in Kuramae, Tokyo, the cooks weave such systems in front of you, describing every detail of the food, and precisely how ‘circular’ it is. For example, elab’s bread is subtly infused with small flecks of cocoa husk, the only residue of the chocolate-making process that the nearby Dandelion chocolate factory cannot find a use for. Dandelion sends it across the street to elab, whose humble alchemy folds it into bread.

One imagines a circular neighbourhood is entirely possible in the resourceful and inventive Kuramae, its streets still patterned by small industrial units, craft work and shop fronts. Information networks, lightweight logistics, adaptable urban design, and committed individuals with shared ideals could weave the whole place together anew. The invisible threads tracing a circle from elab to Dandelion to a network of farms and suppliers beyond might be multiplied and diversified, such that the fabric of Kuramae begins to suggest a circular society with Japanese characteristics.

Movements to Moonshots

Sadly, these shining examples are hardly mainstream. Mass circularity requires an entirely different framing for business and industry, for society and culture, and in how we make shared decisions about shared things. But we can be thrilled by the scale of such agendas. Our journeys might start with humble experiments with everyday experiences, conducted by the likes of Nori Architects or elab. Yet far-reaching systemic change cannot be achieved solely through the ‘bottom-up’ actions of heroic or concerned individuals whilst ignoring the ‘top-down’ superstructures of policy, regulation and financing. Such an approach is not only unethical but also counterproductive, leading to two disconnected flywheels running counter to each other’s progress. The Swedish government’s mission-oriented innovation prototypes perhaps provide inspiration for how to bind these movements together, balancing ‘moonshot’-like technical programmes with social movement-like participative and place-based action.

Successfully running a portfolio of moonshots and movements woven together would include assessing how diverse networks of super-local examples, predicated on regenerative growth enabled by simple, participative materiality, might balance with technology-led projects propped up on traditional economic models, and more complex material flows. Government can subtly stimulate and steer such an array of approaches, if strategic design capabilities for portfolio-wrangling are at the helm. That requires new ideas of what governance is, yet recall the advice of Donella Meadows: the most powerful leverage points in system change concern these fundamental paradigms. We must connect the ‘top’ of engaged governance to the ‘bottom’ of diverse, pluralistic prototypes, to form a circle.

Autumn to Spring

More precisely, we must move circularity from niche to mainstream products, and from Kuramae’s tightly-bound milieu to all of Japan’s industrial and agricultural networks. We must move from throwaway packaging to regenerative supply chains, from Good Cycle Building to transformation of the built environment sector.

The scale, variety and systemic interconnectedness of these challenges poses significant questions. But could an open-minded searching across diverse knowledge systems sow the seeds for authentic circular design practices with Japanese spirit? How might we draw meaningful inspiration from the past before today’s throwaway society? How might we best cultivate and nurture examples in the present, like elab and its kin? How might we fuse both into the moonshots and movements of the future? In all this, might we see the dynamics of a new metabolism? Truly inventive circular design practices might see Japan’s autumn afternoon blossom once again as a new spring.

メルボルン大学大学院 建築学部 デザイン学科のディレクター。前職はスウェーデン政府イノベーション庁 Vinnova のストラテジックデザイン・ディレクター。デザイナー・アーバニストとして、ArupやFuture Cities Catapult、Fabrica、SITRA、BBCなどの世界的な組織で指揮を執った実績を持つ。またロンドンのUCL Institute for Innovation and Public Practiceにて客員教授を務め、国連の「人の住まい」に関わる事業活動であるUN HABITATとロンドンのLSEならびにUCLのジョイントベンチャーであるCouncil on Urban Initiativeの創設メンバーでもある。

Dan Hill is Director of Melbourne School of Design, the graduate school in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne. A designer and urbanist, Dan's previous design leadership roles include the Swedish government’s innovation agency Vinnova, Arup in UK and Australia, the UK's Future Cities Catapult, Fabrica in Italy, the Finnish Innovation Fund SITRA, and the BBC. Dan is also a Visiting Professor at UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Practice and a founder member of the Council on Urban Initiatives, a joint venture between UN HABITAT, LSE and UCL.

2024

2024